Protecting Our Trees

The Urban Forest Preservation Act is the law that governs the District’s urban forest. It states:

“The urban forest of the District of Columbia, growing on both public and private land, is one of the District’s great natural resources”

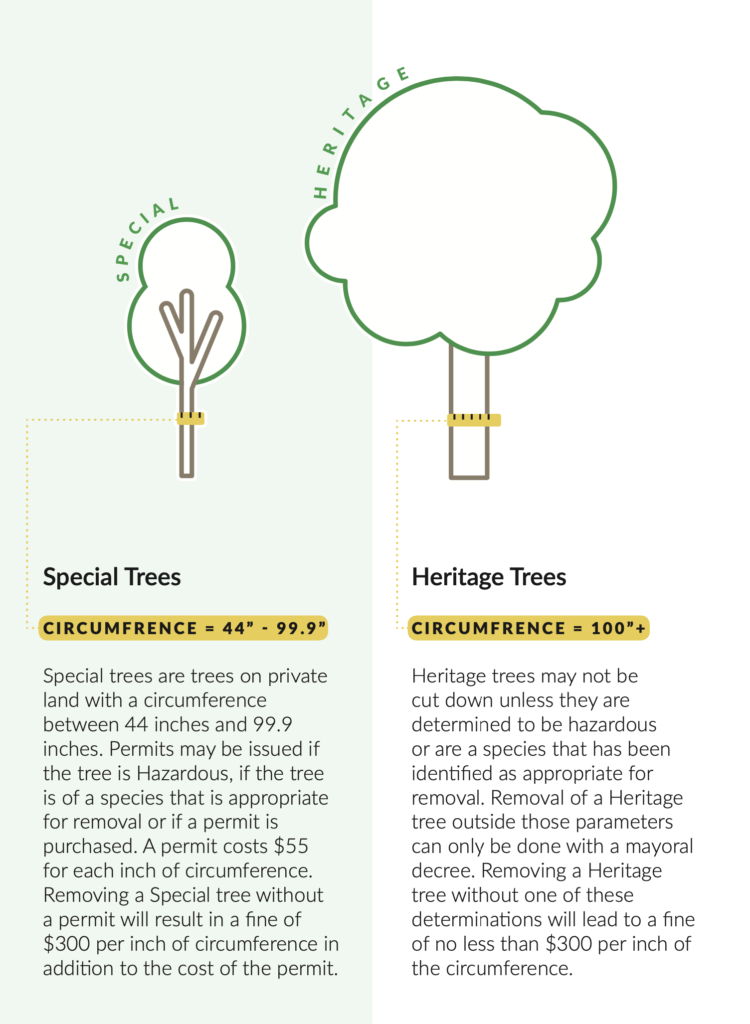

and the trees comprising it have significant environmental and social value. This law protects our largest trees, those with a circumference of at least 44 inches. Protecting these trees is important because our oldest trees are the ones that provide the most environmental, health and social benefits to communities.

If a Heritage tree is illegally removed, there is a fine of at least $30,000 ($300 per inch circumference).

Every year, we see more and more mature trees removed. With only a small number of Heritage trees in the District, each one removed makes a significant impact. Additionally, every Special tree removed is one less tree that has the potential to grow into a Heritage one within our lifetime. Trees provide more than shade on a hot day, they bring a sense of peace to those who live around them and spread a sense of belonging throughout a community. If we continue removing mature trees at our current rate, we risk losing these benefits.

Case Studies

D.C. is changing and with that change comes a new vision of what it means to live, work and play in the District. However, as a historic city, some things remain, including DC.’s urban forest. In neighborhoods across the all eight Wards, you can find trees that are as old as the buildings they cover – they are monuments within the community and because it is illegal to remove them (with some exceptions), developers must design around the existing trees or move them to another location to accommodate their plan. Below are case studies of where developers successfully protected the Heritage trees on their property and where they did not:

Meadow Green Court Apartments – Ward 7

The Meadow Green Court Apartments is a 461 unit affordable housing complex built in the 1940s. In 2019, the owner of the apartments proposed a redevelopment in which they would remove all of the existing buildings and replace them with an updated, more densely zoned complex that would include over 900 units, about a third of which would be affordable. To do this, the property needed to be rezoned through the Planned Unit Development process. This required the approval of the project plan from the Zoning Commission and multiple government agencies. After collaboration with the local Advisory Neighborhood Commission and existing tenants association, a final plan for the redevelopment was approved. In line with the Urban Forest Preservation Act, this plan included the preservation of the more than 30 Heritage trees on the property. The developers did this by keeping the existing layout of the buildings on the property, with apartment complexes centered around a courtyard, where a significant number of the trees are. Vegetation is typically the last thing considered in the planning process; by taking these trees into account from the start, the developers were able to come up with a design that benefits the future and returning residents, the environment and the community as a whole.

The Meadow Green Court Apartments is a 461 unit affordable housing complex built in the 1940s. In 2019, the owner of the apartments proposed a redevelopment in which they would remove all of the existing buildings and replace them with an updated, more densely zoned complex that would include over 900 units, about a third of which would be affordable. To do this, the property needed to be rezoned through the Planned Unit Development process. This required the approval of the project plan from the Zoning Commission and multiple government agencies. After collaboration with the local Advisory Neighborhood Commission and existing tenants association, a final plan for the redevelopment was approved. In line with the Urban Forest Preservation Act, this plan included the preservation of the more than 30 Heritage trees on the property. The developers did this by keeping the existing layout of the buildings on the property, with apartment complexes centered around a courtyard, where a significant number of the trees are. Vegetation is typically the last thing considered in the planning process; by taking these trees into account from the start, the developers were able to come up with a design that benefits the future and returning residents, the environment and the community as a whole.

Former Fannie Mae Headquarters – Ward 3

In 2016, Fannie Mae’s former headquarters was acquired by Roadside Development to be redeveloped into a mixed use residential/commercial space. This new development would include a grocery store, retail spaces, condos and community green space. As a historic building, the developers were limited in their ability to change the building, but modernizations needed to be made to accommodate the building’s new use – this included adding a delivery driveway for the retailers and grocery store. Unfortunately, the driveway was slated to go straight through a Heritage tree. Knowing that this tree could not be removed, Roadside Development asked the Urban Forestry Division for a special exception to allow them to move that tree and two others to another area on the site. After receiving permission, they began the year long process of moving these trees to their new homes. While the price of moving the trees was large, the environmental benefits that these trees are able to continue to provide the community are worth more than the monetary value. More than that, the social benefits of having these trees makes the community space that Roadside Development took the time to save an inviting area where neighbors can gather, interact and build a sense of place.

Sursum Corda Apartments – Ward 6

The apartments at Sursum Corda began as a village supported by religious institutions and, through federal funding, grew into a permanent community. To support the togetherness that initially formed Sursum Corda, the original tenants constructed the complex to have a tree lined courtyard in the center, something that could be used for community gatherings and neighborhood events. Unfortunately, in the years that followed, the community experienced significant hardship and, with high crime and lack of investment in low income communities, the buildings soon fell into disrepair. In 2004, the District government pushed for investment in this community and in 2016, the Sursum Corda apartments were sold to the Toll Brothers development firm.

Despite community support for redevelopment, however, the lengthy permitting process and a change of development plans stalled the process. By 2019, when the Toll Brothers presented their final design for the Sursum Corda apartments, policies had changed – most notably the Urban Forest Preservation Act. Since their initial purchase of the property, the Urban Forest Preservation Act had been amended, increasing the number of trees on the Sursum Corda property that were protected under the act. Instead of only Special trees, the Sursum Corda property now also had eight Heritage trees, which could not be removed unless they were determined to be hazardous or were given a special exception from the government. The developers argued that, because they began permitting before the designation of Heritage trees was created, they should be allowed to remove the Heritage trees as planned. When this was rejected, they pushed for an amendment to the Urban Forest Preservation Act that would give them this exception. Ultimately, because of advocacy by thousands of community members and stakeholder groups, including Casey Trees, this bill was not introduced to the D.C. Council.

Despite community support for redevelopment, however, the lengthy permitting process and a change of development plans stalled the process. By 2019, when the Toll Brothers presented their final design for the Sursum Corda apartments, policies had changed – most notably the Urban Forest Preservation Act. Since their initial purchase of the property, the Urban Forest Preservation Act had been amended, increasing the number of trees on the Sursum Corda property that were protected under the act. Instead of only Special trees, the Sursum Corda property now also had eight Heritage trees, which could not be removed unless they were determined to be hazardous or were given a special exception from the government. The developers argued that, because they began permitting before the designation of Heritage trees was created, they should be allowed to remove the Heritage trees as planned. When this was rejected, they pushed for an amendment to the Urban Forest Preservation Act that would give them this exception. Ultimately, because of advocacy by thousands of community members and stakeholder groups, including Casey Trees, this bill was not introduced to the D.C. Council.

The introduction and/or passage of such a bill would have set the precedent that a developer who did not want to comply with Heritage tree laws could receive a legislative amendment allowing them to ignore the law. Opening up this loophole would have taken the teeth away from the existing checks on Heritage tree removal, making it difficult to enforce. The Heritage trees at Sursum Corda were illegally removed and a fine was paid for that action. No law is perfect and it is important that, when we amend the law, we amend it so it is strengthened, so that loopholes and so that we are increasing protection for our Special and Heritage trees.

These case studies demonstrate that trees are a defining feature of a neighborhood, and when they are removed, it is not just the aesthetic value that is lost. They shield residents from the hot summer sun, prevent flooding during harsh storms and remove harmful pollution from the air. It takes lifetimes for trees to grow to maturity, and even longer for them to get to Heritage tree size. The D.C. government has demonstrated their dedication to supporting the District’s tree canopy by creating Heritage trees, we must continue to advocate for their protection and be diligent in supporting their protection during development.

How are Heritage Trees Removed?

Not all trees larger than 44 inches in circumference are Special or Heritage trees – it depends on who is removing them, the species and whether the trees are a hazard to the people or property around it. Trees are only considered Special or Heritage if the person removing it is an individual or a nongovernmental entity (such as a development firm or construction company). If the government is removing the tree, even if it is 44 inches or larger, it is not considered a Special or Heritage tree.

As a general rule of thumb, it is illegal to remove a Heritage tree, however, there are exceptions. The following describe how a Heritage tree can be legally removed:

Hazardous

A Hazardous tree is any tree that has been determined to be defective, diseased, dying or dead and pose a threat to the people or property around it. A tree can be Special or Heritage and Hazardous, so a District arborist must look at the tree and certify it as Hazardous before it can be removed. You can contact the District Urban Forestry Division or your Ward arborist for questions about a specific tree.

Species

No matter their size or who is responsible for removing them, there are three species exempt from this law: Ailanthus altissima (Tree of Heaven); Morus species (Mulberry); Acer platanoides (Norway maple).

Special permission – Moving a Heritage Tree

A Heritage tree removal permit may be issued if a person wishes to move their Heritage tree from where it is currently located to another place on the property. To apply for this permit, a person must identify the new location within the District and prove that there will not be significant harm to the tree. To be fully in compliance with this permit, the Heritage tree must live for at least 3 years after replanting, otherwise, it is considered an illegal removal and a fine of $300 per inch circumference of the tree must be paid.

“It shall be unlawful for any person or nongovernmental entity, without a Heritage Tree removal permit issued by the Mayor, to top, cut down, remove, girdle, break, or destroy any Heritage Tree”