One of the newest invasive insects to appear in DC, the spotted lanternfly, is not actually a fly but rather a planthopper (a not-so-distant relative of cicadas) that was discovered for the first time in the United States in the suburbs of Philadelphia in 2014. Since those initial detections around a decade ago, spotted lanternfly has spread rapidly with infestations documented in over 15 states as well as the District of Columbia.

The LIFE Stages of A Spotted Lanternfly

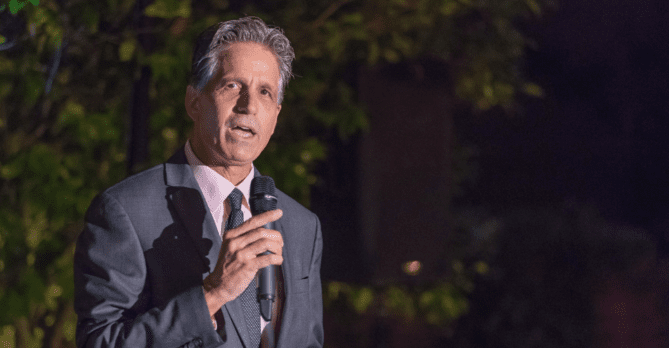

Over the past few months, egg masses that were deposited by adult females last fall on trees and other structures began to hatch around the region. The term “nymph” refers to the immature life stage of true bugs (Order: Hemiptera) and all members of this group of insects progress through multiple nymphal stages, known as “instars.” Early spotted lanternfly instars are black with white spots and crawl and jump as they search for succulent growth to feed on with their straw-like mouthpart (Photo 1). These stages can be seen through about mid-July.

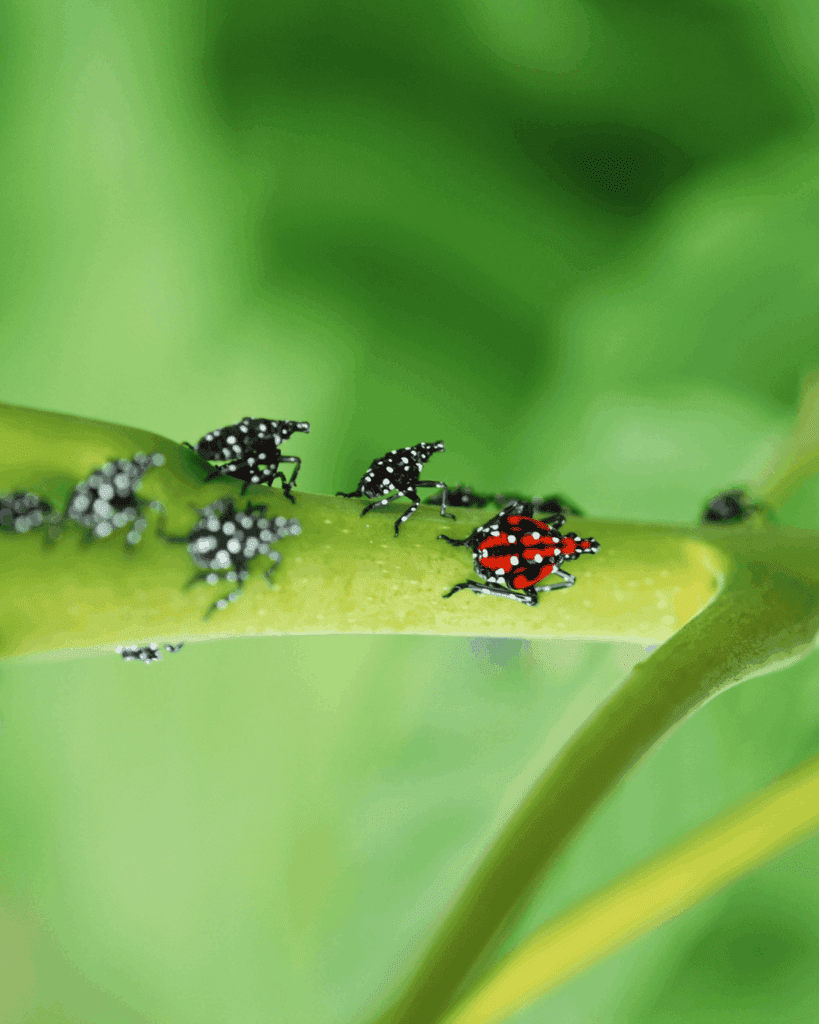

Towards the middle of the summer, spotted lanternfly nymphs reach their final instar stage, when they take on a brilliant red color with black and white accents (Photo 2).

None of these immature stages are capable of flight, but if you look closely at the last instar stage, you can see the developing wing pads that will become fully fledged wings in adulthood.

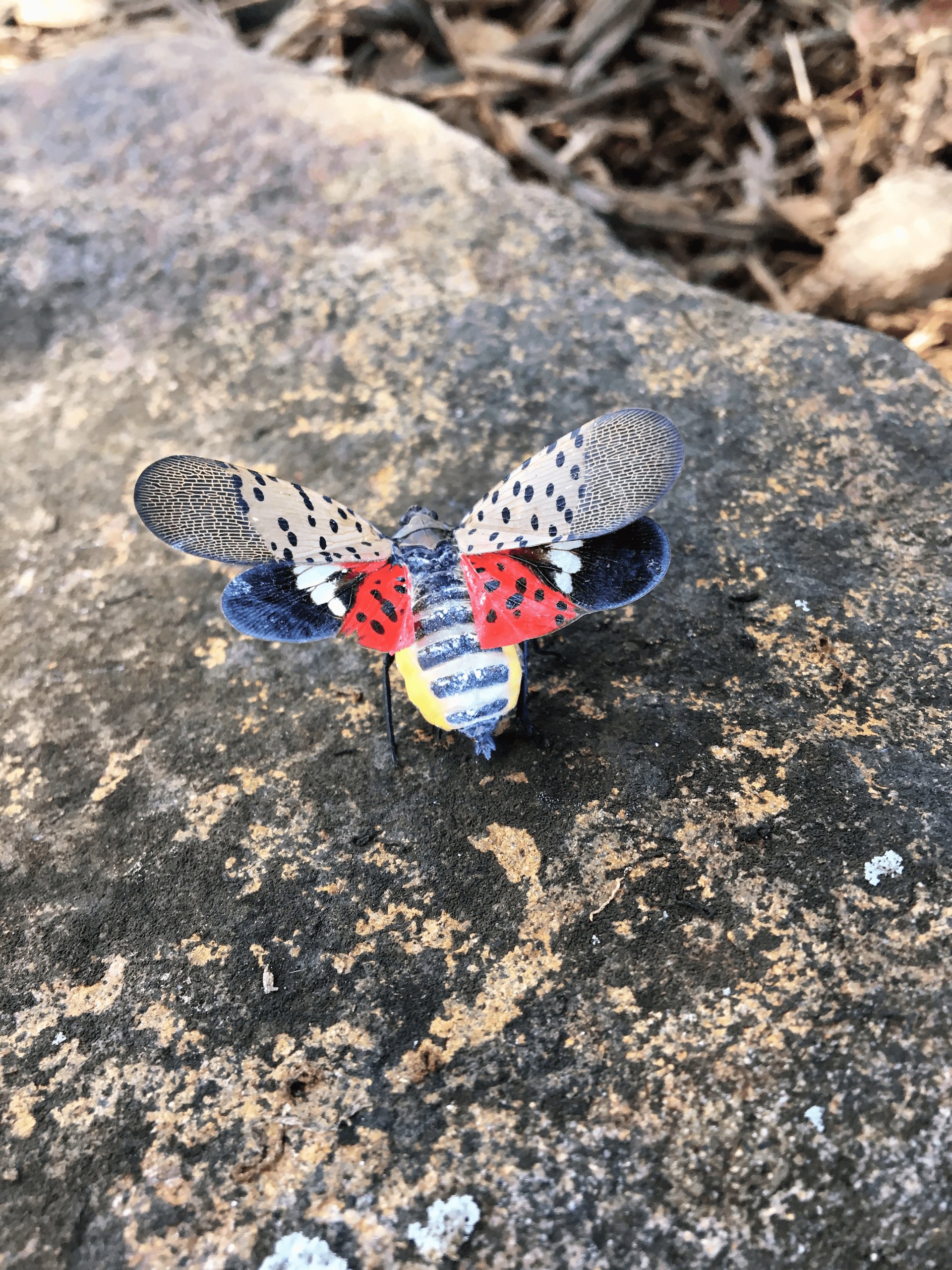

This year, I received reports of adult activity beginning over the 4th of July weekend, but it is not uncommon to see them really make their presence known across the landscape by the time Labor Day rolls around (Photo 3). From tip of the head to the end of the wings, adults can be around an inch in length and can crawl, jump, and fly.

When resting, feeding, or crawling, their forewings are closed and all that is visible are the spots and stripes that still make for a unique and readily identifiable insect in the yard. However, when they are ready for flight, they unfurl their forewings and expose their bright red hindwings, which are what many people see in photos of this insect and can further aid in identification (Photo 4).

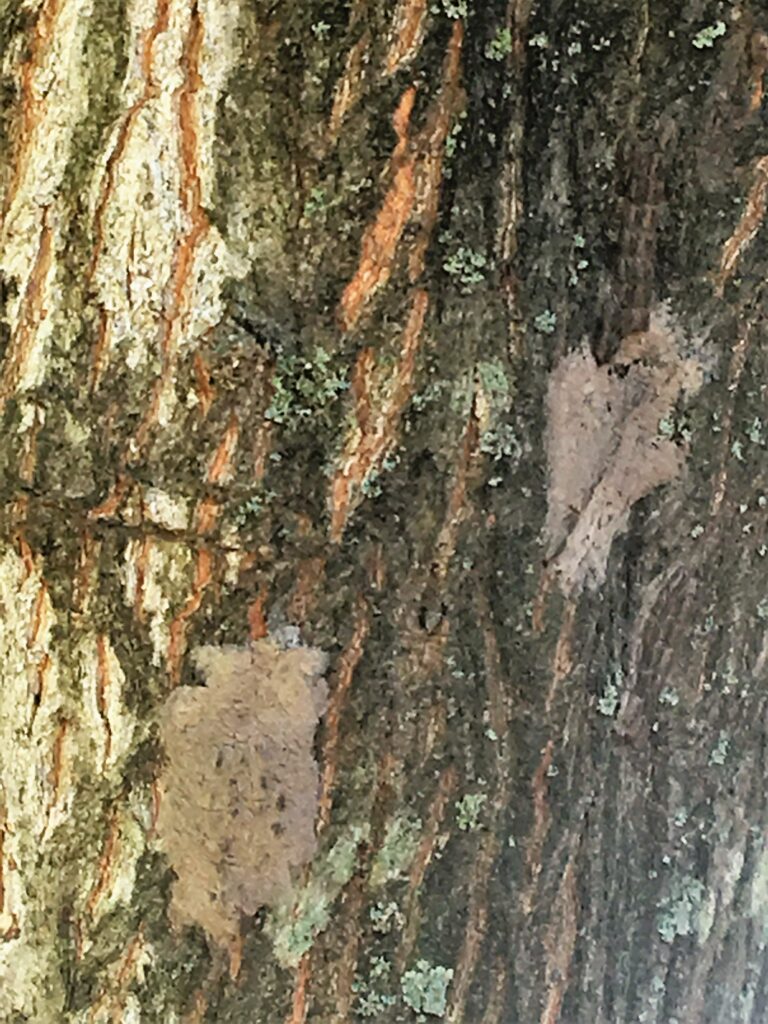

Adults persist in the landscape until the first hard freeze, feeding and mating, and leave behind subtle yet distinct egg masses that will remain over the winter until the following spring where the life cycle is repeated (Photos 5 and 6 below).

WHAT THE SPOTTED LANTERNFLY MEANS FOR YOUR BACKYARD

As far as invasive insects go, I would not consider the spotted lanternfly to be one of the more destructive critters that a member of the public might have to deal with.

Much like with the brown marmorated stink bug, large aggregations in your yard or neighborhood can be a nuisance, but the good news is that the threat they pose to the health of most trees and shrubs in the landscape is not extreme. They can, however, be an extreme nuisance.

As spotted lanternflies feed on plant sap, they secrete a sugary, watery byproduct (similar to crapemyrtle bark scale) called “honeydew” that can cause several issues. Honeydew can make structures (e.g., our patios and walkways) sticky, it supports the growth and development of black sooty mold, and it can attract stinging insects like wasps that view it as a valuable, carbohydrate-rich resource.

While many insect species show a strong host preference at the genus (e.g., oak or maple) level, spotted lanternfly can further cause frustrations with its massive number of documented hosts, meaning some are likely in your landscape. Grape, black walnut, willow, river birch, red maple, and tree of heaven, are a few of the key favorites.

HOW TO MANAGE THE SPOTTED LANTERNFLY

So, what does management look like? Depending on your situation, tolerating their presence as best as possible can be one of the easiest strategies.

You can also try to squish them (if you can catch them). Whatever you choose to do, DC does not recommend using insecticides to kill them due to the harmful impacts they would have on non-invasive species. The Department of Transportation (DDOT) and the Department of Energy and Environment (DOEE) have given advice on managing spotted lanternflies and request that you report sightings.

These bugs, while potentially annoying, pose no obvious, direct threat to human health. There are a multitude of more active management strategies available should you find yourself dealing with large outbreaks or copious honeydew production that have been nicely detailed in this comprehensive management guide provided by Penn State.

Whenever considering any form of pest management, make sure to think about your options and approach them through the integrated pest management framework and don’t be afraid to contact a certified arborist for help!

This article is part of our ongoing collaboration with Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories, which aims to educate the DC region about its insect inhabitants and provide practical tree care advice to residents.

Chris Riley is an Entomologist and Mid-Atlantic Research Scientist and Technical Support Specialist with The Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories. Chris serves as a research collaborator with Casey Trees, providing knowledge and expertise that ensures the health of our urban tree canopy.