Let’s imagine it’s a ‘normal’ summer in downtown D.C. – it’s hot, above 90 degrees say, it’s been hot and humid for weeks, and it feels a bit like the city is under a blanket of summer slowly being baked. Now let’s imagine you find yourself (or see someone else!) in a suit heading to a midday meeting. Which side of the road do you choose to walk on? Wide, concrete sidewalks next to multi-lane roadways with few awnings, small sapling street trees, and full sun or the side that’s covered by large canopy trees, basked in shade for hours? If you have ever crossed the street to walk in the shade of buildings, awnings, or hopefully trees, or chose to wait for a stoplight or the bus in the shade you implicitly know the temperature difference known as urban heat island effect.

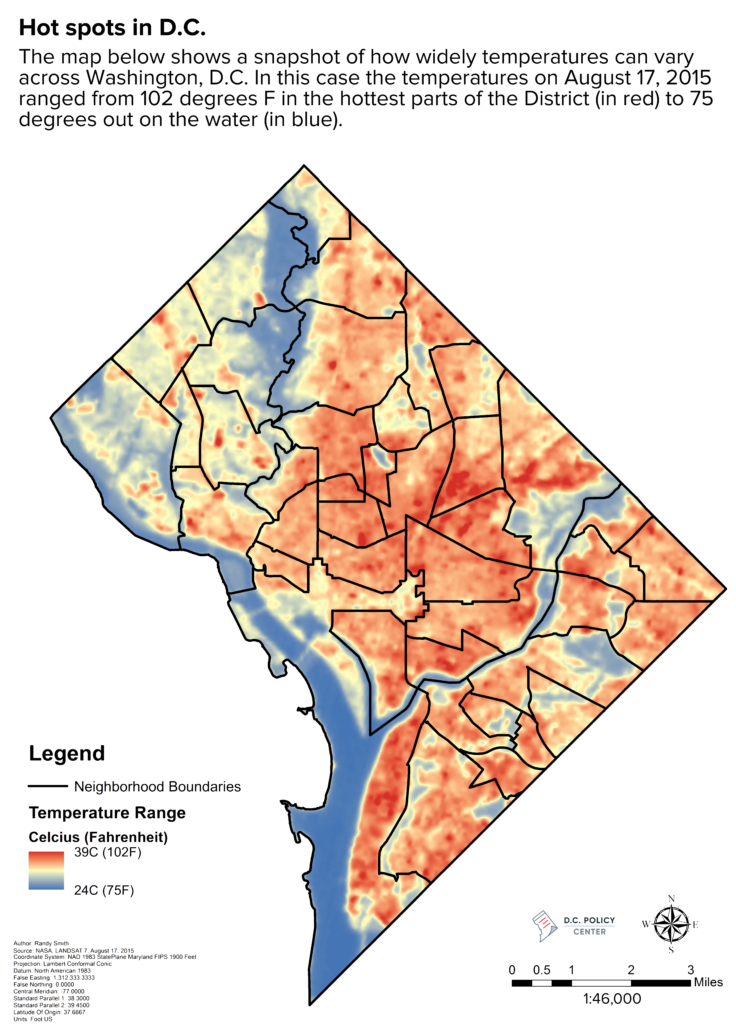

In basic terms, the urban island effect describes the idea that cities are hotter than surrounding rural areas. Asphalt from roads, concrete from sidewalks, patios, and buildings as well as made building materials, all retain heat, amplifying temperatures during the day, and keeping temperatures high into the night. In fact, air temperatures in cities, particularly after sunset, can be as much as 22°F warmer than the air in neighboring, less developed regions!

The prolonged elevated temperatures from our built environment have a wide-ranging, and deadly, set of impacts on the environment:

- Elevated summertime temperatures in cities caused by urban heat islands increase energy demand for cooling. During extreme heat events, which are exacerbated by urban heat islands, the resulting demand for cooling can overload systems and may result in brownouts or blackouts to avoid power outages.

- Companies that supply electricity typically rely on fossil fuel power plants to meet much of this demand, which in turn leads to an increase in air pollutants and greenhouse gas emissions. These pollutants are harmful to human health and also contribute to complex air quality problems such as the formation of ground-level ozone (smog), fine particulate matter, and acid rain.

- Increased use of fossil-fuel-powered plants also increases emissions of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), which contribute to global climate change.

- High pavement and rooftop surface temperatures can heat stormwater runoff. This heated stormwater generally becomes runoff, which drains into storm sewers and raises water temperatures as it is released into waterways, which can be deadly for aquatic animals and organisms.

And in a twist surprising no one, D.C.’s historically underserved neighborhoods bear the overwhelming burden of urban heat island effects. This is not a new phenomenon either, as redlining paved the way (literally) for extreme heat in Black and brown neighborhoods in cities. Redlining prevented minority families from owning homes, fueling today’s racial wealth gap. They also led to decades of disinvestment in already-struggling neighborhoods, which helped shape the current built environment, exacerbating the disparities of the urban heat island effect.

In 2017 the D.C. Policy Center published a report that added more detail to how heat affects Washington residents. It overlaid temperature with social, economic and health-related factors, as well as vegetation variability, to yield what is called a heat vulnerability index. The report found people who live in poorer, historically African American communities in Northeast and Southeast Washington, where many residents rent and have less ability to landscape or plant trees, are more at risk of heat-related illnesses than the people in more well-off communities.

So what’s a city to do? Recognize that the urban heat island affects different parts of the city in different, systemic ways. Work to address those differences (painting roofs white to reflect heat, replacing pavements, planting trees and vegetation etc). But design and planning decisions made by city agencies cannot be the only adjustment – there must be better coordination to understand the bigger picture about what communities of color need and how to include their voices at the table. And that’s on us all. Equity must become the “default” solution.

This is one of the many, connected ways that climate change will affect different geographical and socioeconomic parts of the city differently and even exacerbates current inequalities (like urban heat island effect!).

This is one of the many examples of environmental injustice that we’ll cover as part of our invigorated efforts to consider the racial implications of environmentalism and city planning efforts. As always, we’re open for questions, comments, and critiques at friends@caseytrees.org.