The Camp Fire in northern California has leveled entire towns, billowed ash and smoke impacting areas miles away, and is now the deadliest wildfire in state history. Cal Fire reports it has claimed 48 lives, burned 150,000 acres and is about 65% contained. More than 5,000 personnel are fighting the blazing fire, which has destroyed more than 12,000 homes and buildings.

As an already record-breaking wildfire season shows, wildfires are growing larger and more destructive than ever before due to climate change, drought, a lack of funding for prevention programs and other factors. This makes wildfire an especially pressing issue. Unfortunately, it is frequently misunderstood. Especially with more and more people moving and building homes closer to wildlands, it is vital that we separate wildfire myths and facts.

Myth: Wildfires are an inevitable fact of nature

While wildfires are a natural phenomenon, the extent and intensity to which they’re happening now are not – and one of the effects of climate change. But as the climate has become hotter and drier in the last four decades, the number of fires has increased.

While you can’t point to climate change as causing any particular fire on its own, it does influence factors that help spark and spread fires, like major drought, high temperatures, low humidity and high winds. As a result, the U.S. Forest Service estimated in 2015 that climate change has led to fire seasons that are on average 78 days longer than they were almost 40 years ago.

Myth: All wildfires are bad and must be quenched immediately

Fires have played a crucial role in ecosystems for millennia and life has evolved beside them: some beetles breed only in the heat of fires, pine cones germinate with periodical fires and cleared space from burnt trees allows for new plants to spring.

By fighting wildfires relentlessly during the past century, we have prevented this ‘cleansing’: less than 1% of US fires are allowed to burn. The “suppress at all costs” mentality was eventually replaced with managed or prescribed burnings designed to prevent larger scale, uncontrollable fires instead of fighting them once they’d already begun.

Myth: Technology has dramatically improved and changed the way we fight fires.

Air tankers dropping 11,000-gallon payloads of blood-red fire retardant on flames look great on the nightly news. But the boots-on-the-ground work of stopping fires has changed little since 1910, when a blaze called the Big Burn scorched 3 million acres across Idaho’s panhandle and into Montana. In its wake, the Forest Service dedicated itself to aggressively dousing every spark in the forest.

In the hundred years since the Big Burn, we’ve come to terms with the fact that controlled fires are a natural part of the ecosystem. However, so far, no technology has been able to replace human judgment and dexterity when it comes to culling potential kindling. “The fact of the matter remains you still have to engage the fire, and that means going in and building lines, often by hand,” says fire researcher Jim Cook. And, unfortunately, no matter how many folks you have working, firefighters have as much ability to control a wildfire as the National Guard does to stop a hurricane.

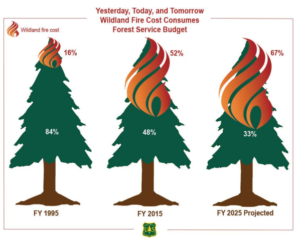

Myth: As wildfires get worse, the Forest Service gets a lot more money to fight them

Today, the wildfire season is 60 to 80 days longer than it was three decades ago, and fires burn much larger areas. The cost of fighting the fires has gone up, too: In 2015, the Forest Service announced that for the first time in the history of the agency, it was spending more than half its budget to suppress wildfires, up from 13 percent of the agency’s budget in 1991. Last year the Forest Service spent $2.5 billion on wildfire suppression.

With costs rising, fire funds often run out in the middle of wildfire season. Meanwhile, total funding for the Forest Service has stayed about the same. This has been a chronic problem, perpetuating the cycle of extreme fire seasons by neglecting activities that help maintain forest health and reduce the likelihood of future catastrophic wildfires.

Myth: Fires are bigger now than at any point in history.

It’s true that between 4 and 10 million acres of forest burn each year, 40 percent more acreage than just 40 years ago. But today’s fire seasons — and even individual fires — are actually smaller than the historic norm. Before the 20th century, almost 30 million acres burned every year. The single biggest U.S. wildfire of the past 50 years, Arizona’s 2011 Wallow Fire, burned a whopping 500,000 acres, but there were at least five fires in the 19th century that blackened twice that many acres. Three of those were larger by a factor of five.

Courtesy NASA Earth Observatory

What’s different about today’s fires is the intensity with which they’re burning. One reason is that fire suppression has changed Western forests. Take the ponderosa stands of the Southwest: Historically, low-intensity blazes, ignited by lightning or indigenous peoples, burned every five to 10 years, thinning the forest of young saplings and brush and leaving just 150 large trees per acre. Today, in the absence of flames, those stands are choked with as many as 1,200 trees per acre — too thick to walk through without risking a branch in your eye. (Plus, remember the role climate change plays – high temperatures and prolonged lack of rainfall wicks water away from plants, drying them out and priming the forests for fire.)

Scientists call the resulting breed of blaze “megafires,” which burn so intensely that firefighters have little hope of containing them.

Ultimately we must learn to live with fires. It will take preparing homes and communities for the worst blazes, letting flames do the good work of thinning trees and intentionally igniting more fires when the time is appropriate.