THE LEAFLET

An Uncertain Future For Private Tree Regulation in Cities

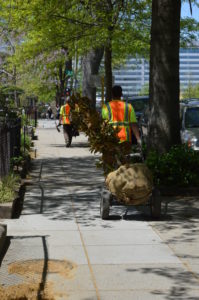

We all know that cities have long regulated what can be done to trees in parks, along public streets or on government property, deciding when they can be trimmed, treated for disease or removed.

But what about private property? Faced with booming populations, cities are treating trees as a key part of urban planning and green infrastructure. The idea is that even trees on private property serve the public good by soaking up stormwater, filtering water for lakes and rivers, cleaning the air and cooling buildings to cut down on energy consumption.

Based on some fiery conversations down in Texas, officials in many cities are bracing for backlash over regulations of trees on private land.

Based on some fiery conversations down in Texas, officials in many cities are bracing for backlash over regulations of trees on private land.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, pushed state lawmakers in a recent special session to scrap cities’ tree ordinances, which he called “socialism,” in favor of a state law stipulating that any private property owner, including developers, had complete control over trees on their land.

“The question comes down to who owns the tree, whose tree is it, and what does it mean to own something?” said Bryan Mathew, a policy analyst with the Center for Local Governance at the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative research group that supported Abbott’s legislation.

Nevertheless, tree advocates are worried. “If this kind of behavior were to take root, it would be disastrous,” said Larry Wiseman, former president and CEO of the American Forest Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for urban trees. “It’s mind-boggling.”

More cities are treating trees as part of “green infrastructure” and are devising urban forest master plans to protect trees — specifically, older trees. Sadly there is no database that tracks how many states are adopting legislation to restrict trees on private property, but Austin has long had among the nation’s most restrictive rules governing private trees.

Where does D.C. stack up? As the City of Trees, in 2016 we approved our own set of stringent rules. “Trees, whether on public or private property, contribute to the livability of the city,” said Earl Eutsler. Protecting “green infrastructure” is as important as maintaining roads, bridges and airports, he said.

Where does D.C. stack up? As the City of Trees, in 2016 we approved our own set of stringent rules. “Trees, whether on public or private property, contribute to the livability of the city,” said Earl Eutsler. Protecting “green infrastructure” is as important as maintaining roads, bridges and airports, he said.

Other cities are moving in our direction too. Atlanta, a burgeoning hub for green infrastructure, is currently rethinking the city’s development plan as its population explodes. Currently, private landowners can remove trees and pay a fine, which the city uses to pay for planting new trees. But “the ordinance is not built around saving trees, people just write a check.” Tim Keane, commissioner of the department of city planning said. The new ordinances would help to reframe the ‘transaction’ around trees as protecting them, not solely generating funds.

Christopher Thayer, an attorney in Seattle who has handled lawsuits about tree restrictions, said he thinks more efforts will be made to cut back on city regulations. “It’s a bit of a shock for people who think, ‘It’s my property, I can do what I want,’ ” he said. And then they find out they can’t.